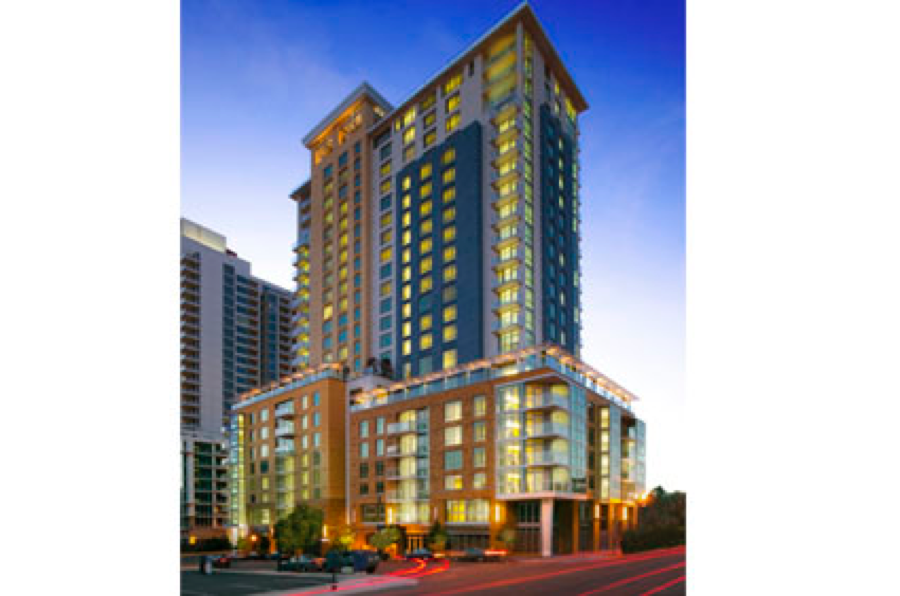

With Fident’s relocation to a downtown San Diego office, I find myself driving by the high-rise affordable housing project Ten Fifty B every day. This 23-story, LEED Gold, concrete, glass, and steel tower is really something. The architecture is good and it offers some of the best views of the city, the Pacific, Balboa Park, and the Coronado Bridge. I’d like to say that the “affordable” project makes me feel good about the inclusionary housing efforts in downtown. Instead, all I see is just how far off target we are in addressing the housing issue.

While housing is a complex topic, the heart of the affordability challenge is the interplay of supply and demand with the cost of construction. I see the supposed solution that Ten Fifty B provides as off target in at least three ways:

- “Affordable housing” operates within a complex and highly subsidized space that provides industry participants a synthetic profit. Should those subsidies disappear, those businesses and these projects would collapse;

- “Affordable housing” accepts and fully complies with all the constraints of high-cost development and the current building paradigm;

- “Affordable housing” does nothing to improve supply.

This phenomenon, if you will, is a wasteful and embarrassing statement on the efficacy of our current governance and its allocation of public resources.

To be clear, the goal of these projects is noble. I’m all for housing people in proper shelter that costs a relatively small portion of income so that families can thrive. After all, as Maslow pointed out, right after food we all need shelter.

But is a LEED project, on prime real estate, with superior views, that costs $400 or more per square foot the answer?

Redirect Public Resource

I am not an affordable housing expert, but it’s the financing that sets these projects apart from all other development. To bring a project like this to life, at such low rents, would be impossible without highly atypical financing. It just doesn’t pencil. Development, and the extraction of profit in affordable projects (yes, there is profit) then hinges on an in-depth knowledge of disparate and arcane financing options and how to effectively stitch them together. A typical affordable project may employ 12 to 18 sources of capital. Low-income housing tax credits, HOPE VI, community development block grants, HOME funds, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) programs, state, county, and city financing and incentive programs represent only part of the diverse ecosystem that supports “affordable” projects.

Without going into academic precision, these funding sources have incentives (mostly budget allocations or tax benefits) which subsidize these deals. Therefore, a developer can earn profit, in the form of fees, for delivering very high quality projects that tenants who comply with regulations can occupy at a fraction of what the cost would be otherwise.

The waste is multi-faceted, and there are a lot of parties at the table. I recently watched the movie Poverty, Inc., which illuminates how those attacking global poverty thrive within a diverse and robust industry that may intend to serves the poor, but that does so at an unexpected and negative cost. As with affordable housing, these incentives (profits/wages) host a wide array of industry participants. Free of market forces, these perverse incentives support a thriving industry. Without subsidy, the entire thing would collapse.

I am confident that alternative allocations of public resource can more efficiently work to solve the problem at hand.

Flex Zoning Constraints

The Ten Fifty B “high rise of affordability” is wasteful. Market based solutions that work well within the existing regulatory environment, like micro-units and co-living, are one solution. Another solution, and one that is more obvious to me, brings some simple flexibility to local zoning codes to build, in a real dollars and cents manner, less costly product which can be rented to those with lower incomes.

The apparent intent of zoning code–to create a safe and cohesive built environment that compliments itself and the community–is good. We need a conductor for all the musicians inclined to play. However, our strict reliance on that code borders on ridiculous. We wrote the code to get utility from it, to improve our lot in life, and improve our communities, not to become beholden to it at all costs. As things change, so too should the code. Our desire to create a homogenous, utopian urban fabric at the expense of allowing our creative genius do what it does, (in this case, solve the challenges of building housing for a reasonable cost) wastes time, energy, and resource.

For example, consider the kids living in a dump in Paraguay who desired to have music a part of their lives, but who lived in an environment where proper instruments were out of the question. The answer? They built instruments from trash. That’s who we, as humans, are. These children have inspired thousands with how they saw a challenge and used their God-given talents to drive a solution.

We’ve got a fair bit more to work with than trash. By dropping parking requirements, allowing for smaller units, allowing higher density, or requiring less architectural rigor, we can allow projects to profit without subsidy.

What’s worse for the noble cause of cost effective housing; to have a bit of a parking problem, or have a homeless problem? To have a development not meet the hallowed “zoning code” or to ask our citizens to pay so much rent that the economic vibrancy of their station in life sees severe impairment?

Loosen Regulations to Deliver Volume

While codes matters, the cost of housing drives almost completely from the supply side of the equation. When we don’t supply enough product, demand wins the familiar Econ 101 battle and prices go up. Rather than throwing money into otherwise infeasible projects, and supporting a synthetic industry, we can reduce housing costs by simply delivering more product.

Our regulatory environment (from statute to bureaucrat) works to ensures safety and the process creates incredible public benefit. But some aspects of the regulations need to be reworked or simply terminated in the name of serving the public good.

Fident works to raise construction debt and joint venture equity all over the West. We regularly see projects in Texas go from concept to ground break inside of one year. In California, projects of a similar nature can regularly take two to four years to get approved. In fact, 12-year projects are not unheard of. This processing holds back supply and increases the cost of housing.

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA)represents a prime example of needed change. CEQA is a self-enforcing statute. That means that anyone, yes anyone, can challenge a project on the basis of CEQA. Valid citizen-based challenges to a project for legitimate environmental concerns are regularly overshadowed by misuse of the statute. Those aiming to stop (or postpone, to guarantee a long and costly process) any development in their backyard become statute “enforcers”. Worse, those with thinly vailed extortion platforms hold developers hostage until a few hundred thousand dollars are paid to resolve the claim. Both parties have effectively subverted the sound intent of the act, to protect the environment. The supply impacts on this one act, for California, are massive.

For Illustration…

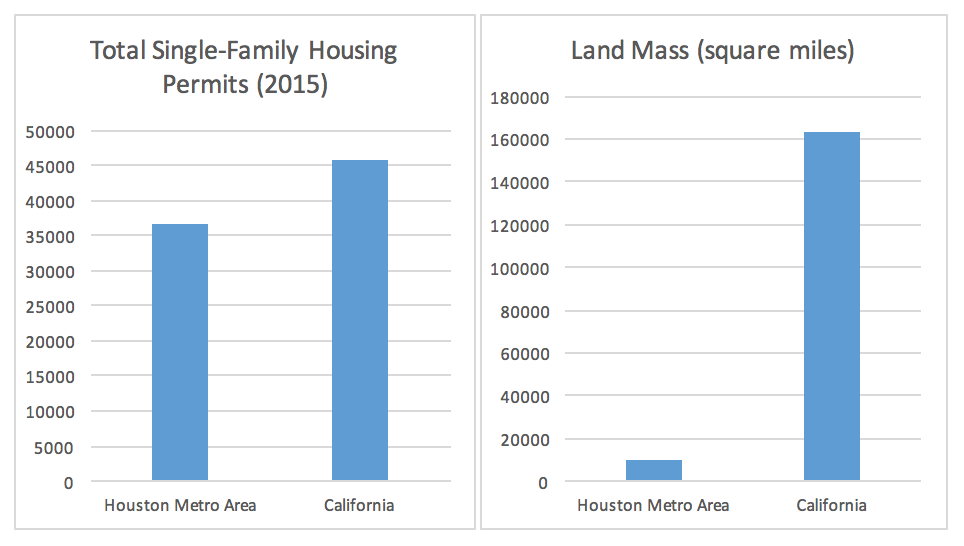

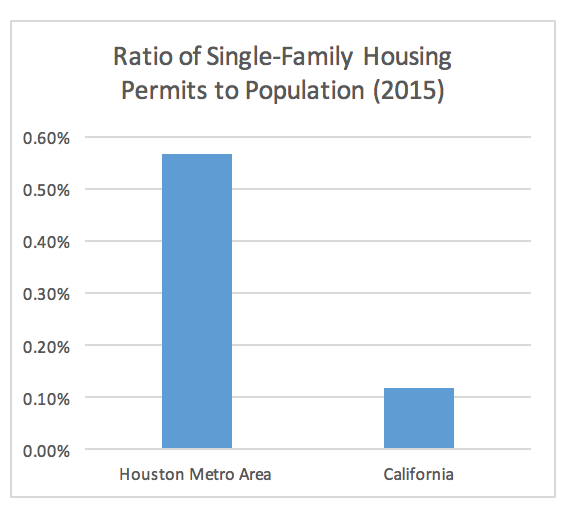

Fun fact: In 2015, the Houston metro area issued almost as many housing permits as the entire State of California, while at a land mass of only SIX PERCENT of California’s.

Taking population into account, the Houston metro area issued almost FIVE times as many housing permits in 2015.

There’s a Better Way. We Need Some Change.

Perhaps the election season has reminded me of the role I too play in our community. We live in the greatest place in the world. We can’t let the system, the government that we created, stop serving our needs and completely lose the plot with something as essential as housing.

I won’t go so far as to say “affordable housing” is a lie. To do so would fail to appreciate nuance that I’m almost certainly unaware of at this point. But the affordable housing industry isn’t our best foot forward, doesn’t represent the best of us when public resources act so inefficiently.

By re-directing public resources to fixes in code, regulations, and statutes, we can find ways to bring real low-cost product, and deliver volume that reflects the job and household creation demands in place. If you fail to see this as an obvious issue, drive down to our office for visit. Just be sure to stop by and visit Ten Fifty B on your way.